The Benefits of Grass-Fed vs Grain-Fed Beef

Currently, there is an unwritten rule that the diet of an animal throughout its life must be at least 51% fresh grass or silage to be labelled as ‘grass-fed’, but only under the threat that anything less than that could make the claim misleading and break advertising rules. However, thanks to organisations such as the Pasture Fed Livestock Association (PFLA), there is now a bit more clarity around these terms and, with it, more assurance of what has gone into a product they are used to describe.

With awareness growing around the impact of intensive meat farming on the health of humans and planet alike, consumers are increasingly looking for assurances that their food has been raised with better impact in mind. When consumers buy grass-fed beef, it is often based on the assumption that the animal has spent its entire life outside, eating nothing but healthy pasture, and it may even be assumed that it has been raised organically. However, unlike the word ‘organic’, in the food world there is nothing to stop the term ‘grass-fed’ being used to describe an animal, even if it has been offered none of these.

Many farmers will occasionally need to offer their animals higher-density food such as grains, for example when the nutrient levels in grass naturally drop at the height of summer, or when their livestock are expecting young. These supplements are known as the total mixed ration (TMR), and for higher-yielding breeds, or for animals recovering from illness, their provision can be very important to welfare. A diet of too much grain, however, can have negative consequences for both the health of the animal and environmental cost.

Given the ambiguity and over-use of marketing terms, for customers who want to know they are eating grass-fed beef, there are assurances they can look out for to make a more informed choice. Currently, the PFLA’s Pasture for Life assurance, found on our Green Butcher range for example, is the only one that certifies animals that have been raised exclusively on healthy pasture and forage.

Grass-fed vs pasture-raised, what’s the difference?

The PFLA have adopted the term ‘pasture-raised’ or ‘pasture-fed’ to describe animals raised according to their standards, as pasture better describes the diverse range of plants available for animals to eat on these farms, including grass, clover, wild flowers and even woodier vegetation such as trees. However, in the absence of a certification of any sort, there really isn’t much standing between grass-fed and pasture-raised, which only means a lifetime on pasture when accompanied by the PFLA mark.

The term grain-fed can represent very intensive systems, such as the grain-dominant Concentrated Animal Feed Operation (CAFO) systems popular in the US, or it can describe animals that have been fed cereals for only the last few weeks of their lives, known as ‘grain-finished’.

Advocates of feeding grain claim cereals such as maize, oats and wheat help animals gain weight, improving the marbling and tenderness of the beef, and that speeding up the process in this way reduces environmental impact – a shorter life emits less carbon, after all. Too much grain, however, has been shown to cause health problems, such as liver abscesses, necessitating the widespread and often indiscriminate use of antibiotics; a practice blamed for the growing resistance of pathogens to vital medications.

For many farmers, grain offers a high-density feed that helps their animals through tougher times, but over 40% of cereals grown around the world are fed to animals, and in the non-organic cases these could be genetically-modified, requiring liberal applications of pesticides and artificial fertilisers. Considering cattle are poor converters of grain, and that the cost of feeding this way continues to rise rapidly, more farmers are now shifting towards feeding their ruminants on pasture.

Is grass-fed beef better for the environment?

Raising ruminants exclusively on grazed pasture and conserved forage (silage) provides a diet much closer to that which they evolved with, enabling the expression of more natural behaviours and preferences, and keeping production closer matched to their natural metabolism. Although it compromises high-yields, making grass-fed beef more expensive than grain-fed, ensuring animals are not to pushed to produce beyond their natural capacity in this way avoids many of the negative consequences of livestock farming.

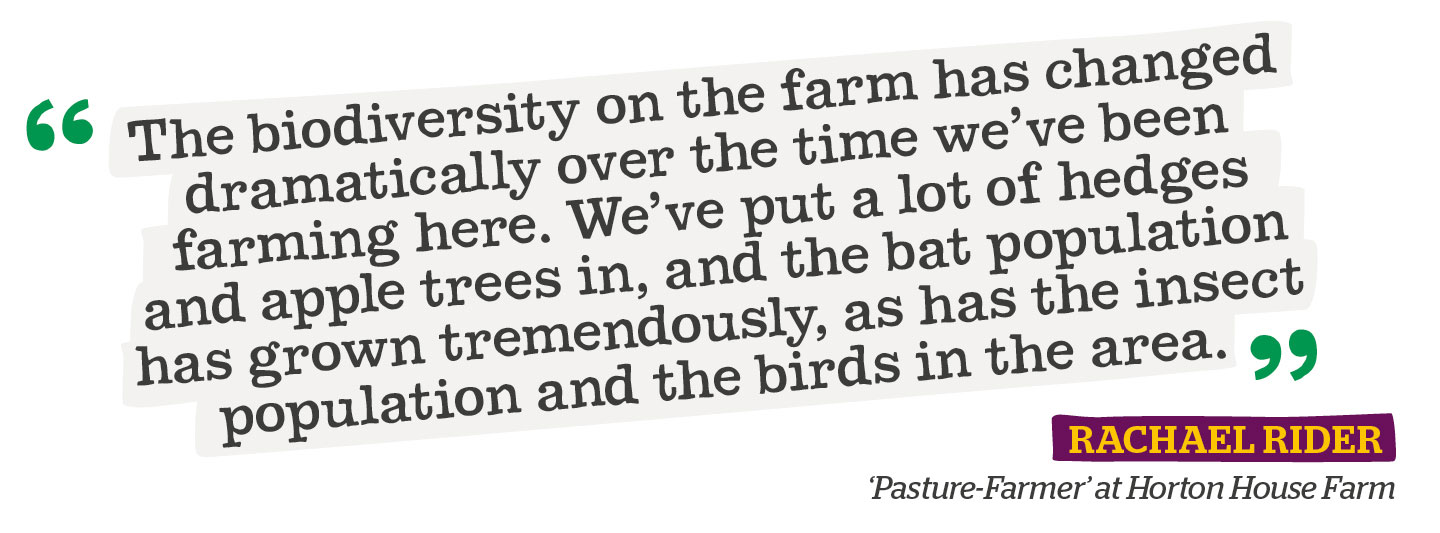

For example, by reducing overgrazing, pasture-fed systems can improve soil health and structure, reducing the risks of flooding and drought by improving water capture and storage. Much of the UK’s native wildlife has evolved with grazing animals and the habitats they create, and ruminants are often employed on nature reserves to maintain biodiversity, a practice known as conservation grazing. Through management techniques that allow more grasses and flowers to seed, pasture-fed systems can increase plant diversity, and initial assessments have shown farmers signed up to the Pasture for Life assurance also observe an increase in birds, mammals and insects on their farms.

The potential for grazing to restore natural cycles extends to carbon too, although the capacity for livestock to offer a solution to climate breakdown is heavily debated (reports and responses, such as Grazed and Confused, and A Greener World, are good starting points for those who want to know more).

Given that the nutritional levels of meat and dairy are heavily influenced by the diet of the animal, eating grass-fed beef, fed only on diverse pasture and forage, could be better for human health as well. Having more clover growing in organic pasture (there to provide the nitrogen that would otherwise be provided by fertilisers on non-organic farms) has been shown to increase omega-3 levels in organic milk by up to 50%, and recent research has shown beef from certified pasture-fed livestock contains twice as much omega-3 as conventionally-raised animals from non-organic systems. Thanks to its abundance in fresh forage, grass-fed beef also contains higher levels of the antioxidant beta-carotene, a source of vitamin-A, giving the intramuscular fat a yellowish tinge.

Having a slightly different composition means pasture-raised meat cooks a bit quicker too, requiring a lighter touch in the kitchen, which also preserves the fresh flavour better.

Organic farming standards require cattle to have access to grazing pasture whenever weather conditions allow, and for at least 60% of their diet to be grass or silage. Organic certification provides an assurance that an animal has been provided a diet free of GMOs, that medication has not been used preventatively, and that fertilisers and herbicides have not been applied to their pasture, but it does not guarantee that grains have not been fed.

Both sets of standards, however, require a similar, restorative approach, and achieving both, like our pasture-fed range, is considered by many to represent the most sustainable way to produce meat and dairy.

Published April 2022